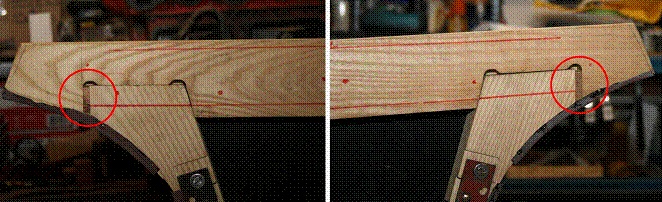

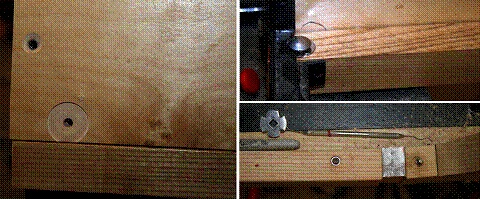

Here are a few more observations along with

the last pictures of the tub wood prior to final fitting and

assembly. Here, inside the red circles, are oak shims

(any hardwood would do) glued inside the scuttle rail to latch

pillar joint to fill and tighten up the joint. Note; best fit to

sheet-metal front quarter panels on this tub with Seabrook’s wood

was a scuttle rail tight against the front surface of the latch

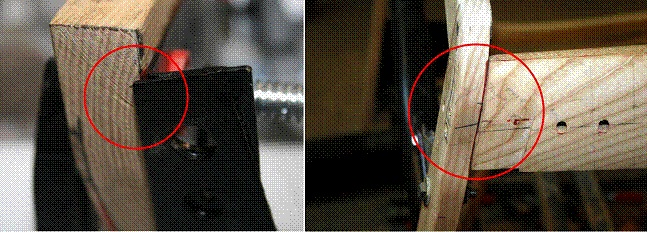

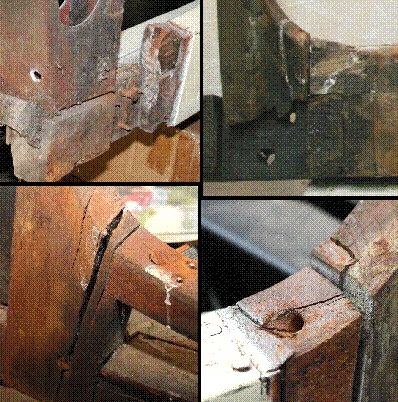

pillar inside the joint. Here’s a shot of the front surface of the

dash side bracket on the drivers side and the misalignment problem

that had to be fixed to achieve the nice tight joint at right. It

seems the two parts of the bracket were welded together out of

alignment. When the bracket is tight against the inside face of the

scuttle side rail a piece of the bracket protrudes into the joint

area. I know it will all be hidden by the sheet-metal, and it

doesn’t seem like such a big deal; but it will prevent the inner

side rail and scuttle side from forming a strong, smooth, flush

fitting joint. There is an easy fix, either grind off the offending

piece of bracket metal for a flush fit, or relieve a small portion

of the front face of the scuttle side rail. I decided to leave the

original bracket, along with this misalignment, intact and make my

repair to the replacement wood. Ah yes, just one more thing that

needs checking as assembly progresses. Both inner front side rails needed a bit of

shortening for a flush fit with the base of the bottom main rail.

Here I’ve marked the line for the final fitting of the bottom of the

driver’s side inner front side rail. There’s that 105 / 75 degree

angle set again. Now when it comes time to fold over the front

quarter panel’s lower nailing flange it will lie nice and flat

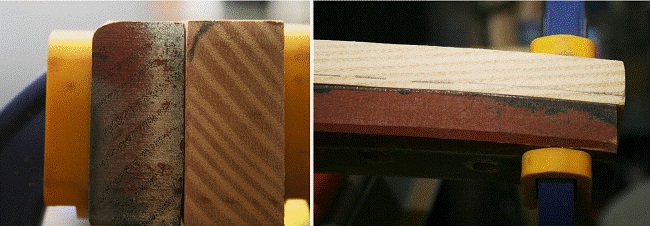

across this joint. Here’s the top inner front top rails, both

old and new, clamped back to front, for marking bolt and screw hole

positions. Center both rails on center of cross-piece slot and along

the top upper edge of both rails. While Seabrook’s top rail is a

spot-on match to the original along its top edge I needed to trace

along bottom of old rail onto new rail and remove any excess wood

along this lower surface to duplicate curvature along the bottom of

my original piece. The cross-piece slot on Seabrook’s piece will

also need a bit of widening for proper fit with cross-piece. Outer top edge of inner top rail will need to

be ‘radiused’ slightly to match the original. Notice how original

top rail is slightly shorter than Seabrook’s piece when centered on

the crosspiece slot. This longer length (about 1/8 inch on each end)

actually fits my tub better than the original. So don’t cut this to

length to match the original as that may leave it a little to short

for a tight fit. Test fit first to ascertain proper length, My door wood was OK for now, the only

problems was one of the original door latch mounting plate machine

screws had become inseparable from it’s capture nut and broke off

when I attempted to remove it. Also the sheet-metal door skin had

begun to pucker underneath the escutcheon screws that hold the door

handle to the front of the door. Both screws had begun to pull away

from the wood door latch pillar. The door-skin sheet-metal was all

that was holding the screws in place as the wood surrounding them

had rotted away.

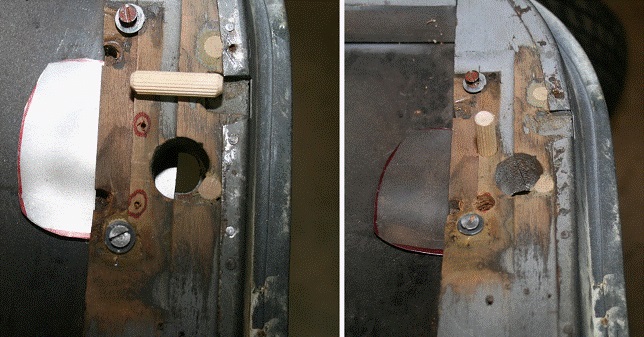

This is a fairly easy fix if the door wood is still solid and

just the screw holes are rotted out and no longer to size. Use a

small diameter drill bit and drill pilot holes through the original

screw holes from the handle side of the door. Next take an

appropriately sized drill bit and from the latch side of the door

use the pilot holes to drill holes for 3/8 inch fluted hardwood

dowels (available from hardware stores and home centers). I slipped

a thin piece of scrap sheet-metal between the door latch pillar and

door skin to prevent the 3/8 drill bit from engaging the screw holes

in the door skin and inadvertently enlarging them. Once holes are of

proper size use a good quality water proof wood glue to coat the

dowels and lightly After the glue has dried, cut off the excess

dowel, sand smooth, and re-drill pilot holes for the door handle

escutcheon screws and mount the door handle. Also visible is an

earlier dowel repair for fitting new door lock screws. This way it’s

not necessary to go to a bigger screw size, which may not look or

fit as well as the original. As for the door latch mounting plate machine

screw problem just drill out the original hole for either a #8 or

#10 stainless steel threaded insert and problem solved.

I also used these stainless

steel threaded inserts to attach the door striker mounting plates on

the new tub latch pillars as opposed to capture nuts as used

originally. I kind of like keeping the hardware on the side of the

piece not covered up by sheet-metal. And besides it won’t be

noticeable once the latch and interior door panels are in place. Hopefully this won’t happen to you but; if,

when test fitting your doors and drilling

holes in the hinge pillars for the screws- things go terribly

wrong- as they did for me and the upper passenger side hinge(the

back of the door set proud of the rear quarter panel) when I got

everything all tightened down. Drill out the holes for appropriately

sized fluted hardwood dowels. Then after the glue has dried just cut

off the excess dowel, sand smooth, and re-drill. Note to myself;

next time measure and mark hinge a little better! Here are some miscellaneous shots of; on the

left, the inletting necessary to use stainless steel torque washers

and carriage bolts on the lower rear corners of the tank panel so as

to not leave the bolt head ‘too proud’ and distort the lower corner

of the quarter panel as it overlays the bolt head. On the upper right is the carriage bolt with

inletted torque washer at the lower inside rear corner of the tub.

These torque washers are 1 1/16” diameter so inletting was done on a

drill press with a 1 1/8” forstner type wood bit. (There is a top

view of one of the torque washers in the shot at lower right.) On the lower right is a picture from above of

the top of the driver’s side under door rail attached to main sill

rail with stainless steel pocket screws. Pocket screws have an

integral washer below the head so as to have a flat bottom with a

larger surface area in contact with the wood. This gives a much

better clamping action when tightened and does not tend to split the

wood over time as a normal flat faced tapered head wood screw may.

Unfortunately these pocket screws have a slightly smaller shaft

diameter so if I was not gluing these joints together I would opt

for a standard wood screw but perhaps replace the original flat

tapered head style with a round head (maybe with a small washer

underneath the head) and just inlet it a little deeper to clear the

sheet-metal. My original under door rails had both split

at their hinge pillar/under door rail joints. Splits extended from

the two outermost under door rail screws along the grain to the end

of the rail. The passenger side joint pretty much just fell apart

when I removed the sheet-metal quarter panel. The latch pillar/under

door rail joints showed splitting as well only not as severe. It’s

these observations, along with my desire to go vintage racing, which

has prompted me to screw and glue together all the wood to wood

joints on this particular TD tub. I think it better for the whole

tub to react to stress and flex ‘as a unit’ and not just at the

individual joints. I

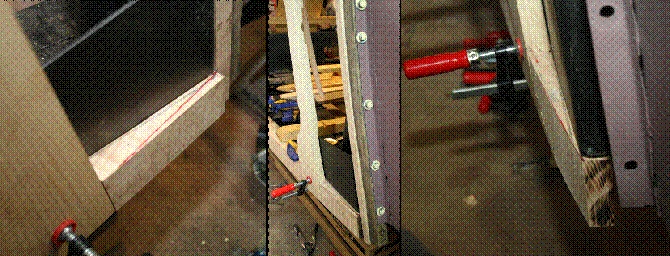

suppose time will tell if that was the right decision. Finally, after I matched up and drilled all

my bolt holes in the two inside front side rails (once again using

the originals as templates) I bolted and clamped everything together

for another trial fitting. I noticed the front tapered portion of

the bottom main rails were sitting slightly proud of the inner side

rails. This would not allow the lower front corner of the front

quarter panel’s nailing flange to properly overlap the front edge of

the inner front side rail. I know, that’s a real mouthful; but I

believe the pictures show what I’m trying to describe. In my case I

just needed to increase the rate of taper to just meet the front

outer edge of the (metal) body frame rail. Now you could just take a clamp and force the

outer end of the bottom main rail inboard and use the inner side

rail attachment point to hold everything in place; but

inward movement here acts to ‘open up’ the latch

pillar/bottom main rail joint. Not a good idea. Especially if glue

is not going to be used, all joints should be as tight as possible

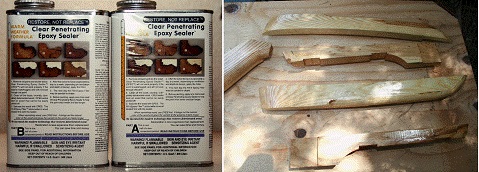

both front to back and side to side. Here’s the stuff I‘ve decided to use on all

the tub wood to help preserve it. It’s from the Rot Doctor (Smith

and Company) specialists in industrial and marine synthetic resins.

They have found a way to save old, dry, rotten, deteriorating wood

and just like the label says it’s a clear penetrating two part epoxy

sealer that does not decrease any of the woods original flexibility.

It’s used a lot on wooden boat restorations and anywhere else wood

needs long term protection from the elements. It’s certainly not

cheep but it does go a long way on new wood.

What the heck, if it works on boats why not an MG.

Finally, with the exception of overlapping

joints which were to be glued, I painted all wood surfaces visible

from inside the tub with a satin black paint to duplicate the

appearance of my tub’s original wood. I used ‘rattle can’

Rustoleum’s satin black; but now that the tub is finished I believe

it’s a little too ‘glossy’ for my taste- probably should have used

another brand. Some tools I’ve found useful. Besides the more familiar screwdrivers,

wrenches and hammers, I thought I would quickly touch on some of the

other types of tools I’ve found the most useful. This is mostly for

the non-woodworkers, folks who are perfectly comfortable with- steel

on steel- type auto body work, but feel a tad lost when it comes to

a ‘T’ series tub wood restoration. Just read a few manuals, take

lots of notes, lots of pictures, and take the time to understand how, maybe

even why, the tub is constructed like it is. After all it’s really

just a big piece of furniture, kinda like a big ol’sheet-metal

upholstered chair. On the left is a Japanese Special Rasp 10”

long and 1 1/2 “ wide with a course and a fine side, looks kinda

like a bunch of hacksaw blades riveted together; but man does it get

the job done! Works so much better than that old style ‘cheese

grater’ plastic filler file I’ve used for years for rough shaping

wood. A little expensive at $34.80 but man does it make quick work

of shaping wood (garrettwade.com). And it leaves a surface that

finishes off nicely with only a bit of work with 80 grit sandpaper.

On the right, some form of angle finder is also helpful to check

your tub wood’s critical angles before disassembly for later

duplication during reassembly. These are the cutting tools I used the most

often, on the left, an old disc sander with adjustable, tilting

table (rescued from dumpster behind the shop where my son works) and

to the right, a Dremel type rotary tool with a flex shaft

attachment. The disc sander for sanding pieces to length, the Dremel

with flex shaft for grinding the heads of panel nails, as a cut-off

tool in tight places for rusty bolts and machine screws, and for

cutting out small areas of rust perforated sheet-metal for fitting

patch panels. Now this is just a suggestion; but for the

most part I left my table saw alone. With a saw I find it very easy

to remove to much wood. For me it worked much better to just use the

disc sander. And ‘in a pinch’ even the under door rail could have

been re-profiled with that Japanese Rasp, it just would have taken

longer. I’ve found, by marking the piece of wood where it needs to

be for an exact fit and using a disc sander to shorten the wood a

little at a time till it fits, I’m not as likely to cut it too short

the first time and have to use a shim. With the disc sander I can

even set it up to sand compound angles if I need to. I find I have a

greater amount of control, even when I just need to eyeball it for

that last 32nd of an inch needed for a perfect fit. Especially with

Seabrook’s wood. I can sand a little then check for fit, then sand a

little more and check for fit again , all the while –‘sneaking up’

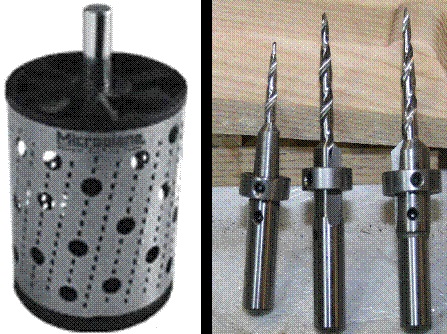

on my pencil or scribe mark. Here’s a close-up of the two inch, Rotary

Shaper drill attachment I spoke of earlier used to shape the under

door rails. (from www.us.microplane.com) and finally on the right a

set of taper point drill bits. These have removable counter

sink/counter bore sleeves and stop collars sized for #6, #8, and #10

wood screws. Use these to drill tapered holes for an exact match to

the screw’s taper. But don’t over-drill the hole or you’ll lose the

benefit of the taper. (from www.rockler.com, and www.garrettwade.com) I also plan on using SAE stainless steel,

slotted head wood screws, machine screws, bolts, and lock-washers

and Loctite where visible, nylocks where not. For an original

appearance all external bolts such as bulkhead, staybars, etc. will

remain whitworth. Inside

the tub the painted over slot headed stainless steel screws will

look original but hopefully have a little more corrosion resistance

than the originals. I’ve found boltdepot.com to have a good

selection with acceptable quality. Also I’m going to try using

stainless steel, four point, square hole, torque washers (from

www.mcfeelys.com) inlet into the wood under all the carriage bolts,

as recommended by Alan Alderwick on page 34 of his book, to prevent

the bolt from both sinking into the wood and spinning when

tightened. This will hopefully allow for some retightening as well.

The 3/8 inch stainless steel carriage bolts had a tendency to gall

when tightened, however I had no galling problems with the smaller

sizes. That being said, I still used just a very small dab of

anti-seize on most of them just in case. So, there you have it. Hopefully these

pictures and insights will be of help as an addendum to the

excellent ‘T’ series restoration manuals mentioned previously. To go to Part 1 click

HERE. For more total assembly information click on

KelleyTubAssembly.doc A Word file)

Ttalk.info

TD Tub Assembly by Hiram Kelley

Part 2

Click Here

for Part 1